By Jameson Coombs*

Unlike trade, Australia's foreign investment position and capital flows are heavily concentrated towards the US. The Trump Administration's proposed section 899 provision poses a significant risk to Australia’s $27.9bn of annual income generated from US assets. This has implications for Australia's US asset allocation and expected investment returns. For the US, it's likely to be another case of economic self-harm.

The focus of recent months has been the potential downside risks to the Australian economy from the imposition of US tariffs. We’ve highlighted that Australia is relatively sheltered from tariffs given.

- The US accounts for less than 5% of Australia’s goods exports, and of that only 40% will face a higher tariff;

- Many of our exports are not readily substitutable with US produced goods and/or can be redirected;

- Most of our exports to China are consumed or used in China’s domestic market;

- China will do what it takes to reach its growth target;

- Australia has been levied the lowest tariff rate, potentially making its exports more competitive versus other nations with a higher tariff rate; and

- The floating exchange rate will help absorb negative external demand shocks, a stabiliser that’s not yet been a significant feature.

The obvious caveat to this is a broader escalation to a global tit-for-tat trade war which would have significant ramifications for global growth and trade. This scenario would entail a larger impact for Australia, though this is looking like an increasingly low probability event.

What’s received less attention, but could be equally consequential for Australia, is the Trump Administration’s crusade on taxing foreign holdings of US denominated assets. The section 899 provision of Trump’s ‘big beautiful bill’ poses a significant threat to the existing flow of global capital.

Section 899

The bill, which has been approved by the house of representatives and is currently before the senate, would give the US Treasury sweeping powers to nominate ‘discriminatory foreign countries’ that it deems imposes unfair taxes on US businesses. Income generated from US assets held by these designated nations would be subject to a 5% withholding tax, which is proposed to increase by 5% each year until it reaches a cap of 20%.

The definition of ‘discriminatory’ in the draft legislation is very loose, with significant discretion ultimately sitting with the Treasury Department. Australia’s Diverted Profits Tax (DPT), Multinational Anti-Avoidance Law (MAAL) and Undertaxed Profits Rule (UTPR), which all seek to counteract multinational profit shifting for tax minimisation, are likely to come into the cross hairs if the bill is passed. It has been suggested that even the media news bargaining code is likely to draw scrutiny from the US Treasury.

The US Senate recently released proposed changes to section 899 reducing the maximum withholding rate to 15%, delaying the implementation until 2027 and exempting portfolio interest, namely US Treasury securities, from the policy.

It’s impossible to predict the policy’s final form if passed, or if it passes at all. However, there is clearly appetite within congress to introduce a lever for manipulating capital flows. And it seems that this is intended as another bargaining chip rather than an avenue for reshaping the composition of US foreign liabilities. Either way though, we are likely to see a policy of some form legislated during this administration.

Australia’s Exposure

Australia’s trade exposure to the US is small, but it’s foreign investment position and capital flows are heavily concentrated towards the US.

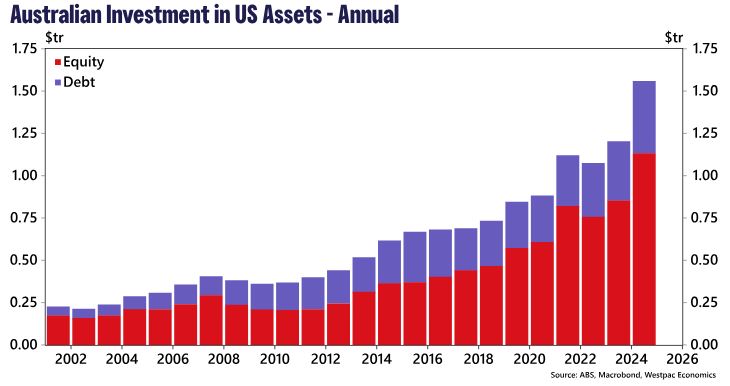

At AUD$1.5tr, 36% of Australia’s offshore investments are in the US, equivalent to almost 20% of all household financial assets. Our US share of foreign investments has increased substantially since 2020, though it may have declined more recently in response to Liberation Day and the end to the US’ exceptionalism narrative. Additionally, almost 75% (AUD$1.1tr) of Australia’s US domiciled investments take the form of equity, rather than debt. In fact, Australia is the world’s 10th largest foreign holder of US corporate equities.

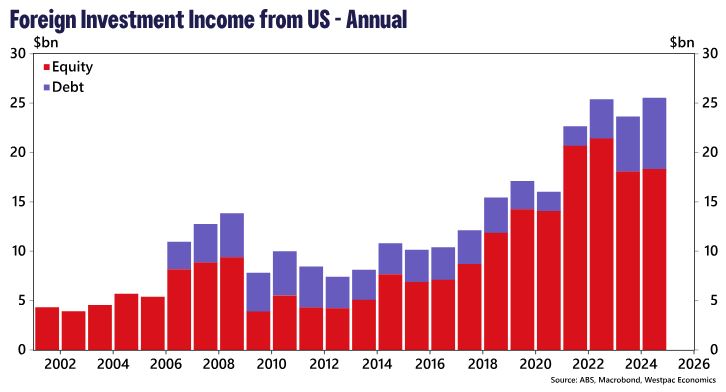

In 2024 our US investments generated AUD$27.9bn of income with AUD$18.3bn attributable to equities. Even with a watered-down section 899 which only applies to equity income, this would equate to an annual tax bill of $900m at 5% or up to $3.7bn at 20%. This is a significant catalyst for considering a re-allocation of our exposure to the US.

The discussion so far has been about Australia’s gross asset exposure to the US. But the US also owns a considerable amount of Australian Assets, around AUD$1.4tr or 27.3% of all Australia’s gross foreign liabilities. That said, Australia holds more US assets than the US holds Australian, meaning we have a net positive asset position with the US. The large value of US investment in Australia does give us scope to ‘retaliate’, though it’s very unlikely we would seek to weaponize our capital account, nor should we. Hence, it’s the gross assets we hold in the US that are impacted most.

The Upshot

Clearly, section 899 poses a significant risk to our existing foreign asset allocation. If passed and applied to Australia, section 899 would provide a material reason to reconsider our exposure to US assets, unless expected rates of return were to rise substantially to offset the impact of taxes (which appears unlikely).

Regardless of the magnitude of any re-allocation of Australia’s assets, section 899 would likely result in lower returns on our foreign investment. Partly from a lower after-tax return on US assets, but also because any reallocation will likely be into assets with lower risk-adjusted returns than currently available in the US (otherwise, we would have that allocation already).

The proposed tax changes are likely to be another case of economic self-harm for the US. Unless by some miracle the US can arrest its huge current account deficit, it will ultimately need to attract capital from elsewhere fill the void from any reallocation away from the US caused by section 899. Without this, the real economy would go through a painful contraction.

The Trump Administration appears to be betting that the US’ role at the centre of the modern financial system and the fact that there is currently no alternative to some US assets (such as the treasury market) will mitigate the impact of the policy on inbound capital flows.

However, this is a sizeable gamble that could ultimately result in a slide in US asset valuations if impacted foreign buyers reduce their exposure and there is insufficient alternative demand to replace them at prevailing prices. This compounds the risk to Australia’s large US asset position.

Unlike tariffs which take time to flow through supply chains and trade flows, financial market shocks like this can have an almost instantaneous impact on capital flows.

It’s not all doom and gloom though, with every disruption comes opportunity and the aftermath of section 899 could provide Australia with an opportunity to attract more global capital that is pushed away from the US by the new provisions. This could supply some of the capital needed to fund the energy transition, with the Trump Administration’s turn away from renewal energy investment an opening for Australia to vie for a leadership stake – as we know there is a large pipeline of renewable investment projects which are required to hit 82% renewables by 2030.

Jameson Coombs is an economist at Westpac.

Comments

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments.

Please to post comments.