By Pat Bustamante*

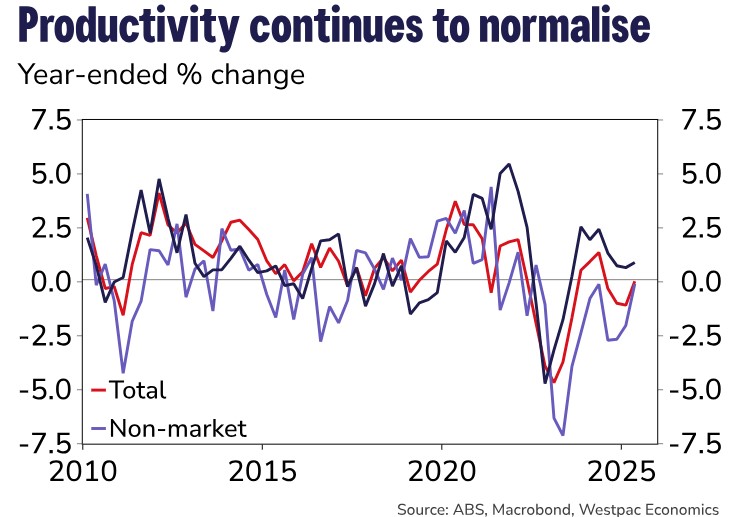

Productivity growth is normalising as the drag from mining and the expansion in the non-market sector fades. Productivity in the market (ex-mining) sector is running at 0.9%yr – in line with the pre-pandemic decade average.

The market ex-mining (or ‘domestically oriented market’) sector accounts for around 70% of hours worked across the economy and is the primary driver of underlying domestic inflationary pressures. Industries in the broad sector include: retail, wholesale, recreational services, business and professional services and construction.

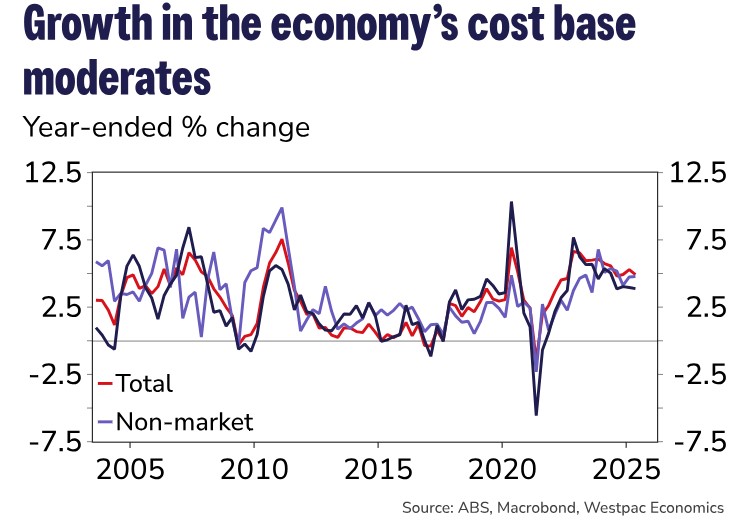

This is seeing growth in the economy’s cost base (or unit labour costs) moderate. For the domestically oriented market sector, this has slowed to around 3.8%yr – in line with 2019 levels and down from a high of 7.7%yr recorded in Q4 2022. In the other sectors, which are not directly relevant for domestic inflationary pressures, costs are growing at a higher rate, but even here we are seeing a moderation as productivity continues to normalise.

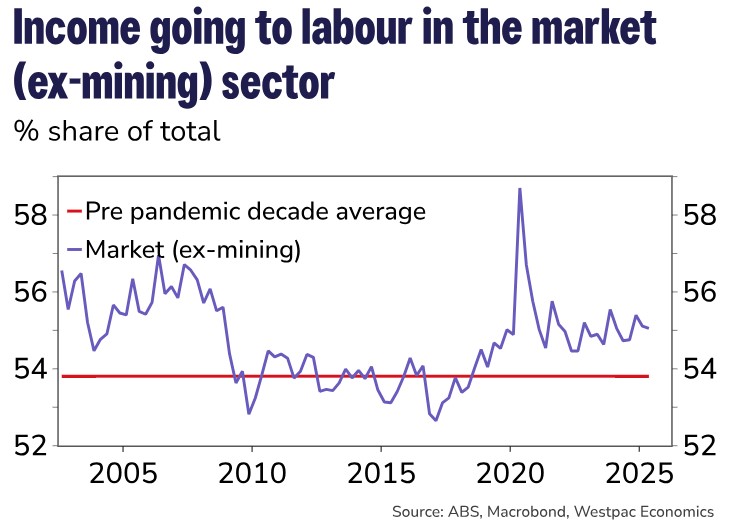

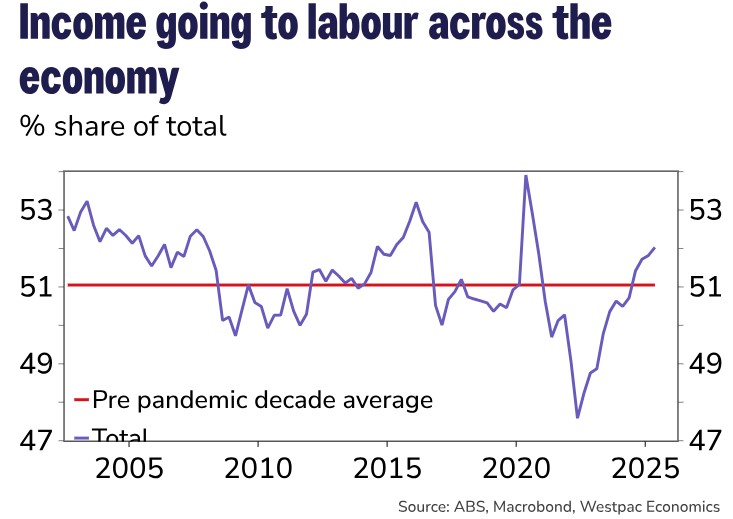

Notably, the weak demand environment means businesses have not been able to fully pass on higher costs to final consumers. With labour costs rising this has seen an increase in the share of income going to labour. Indeed, this share has increased by almost 3ppts compared with the pre pandemic decade average in the domestically oriented market sector and by around 2ppts across the Australian economy. The share in the domestically oriented market sector is approaching the peaks seen during the terms of trade boom, when labour market conditions were extremely tight.

The strong showing in the domestically oriented market sector is flowing through to the broader economy, with the share of income flowing to labour higher than the pre-pandemic average. In the non-market sector this share is around average levels and has fallen in the mining industry.

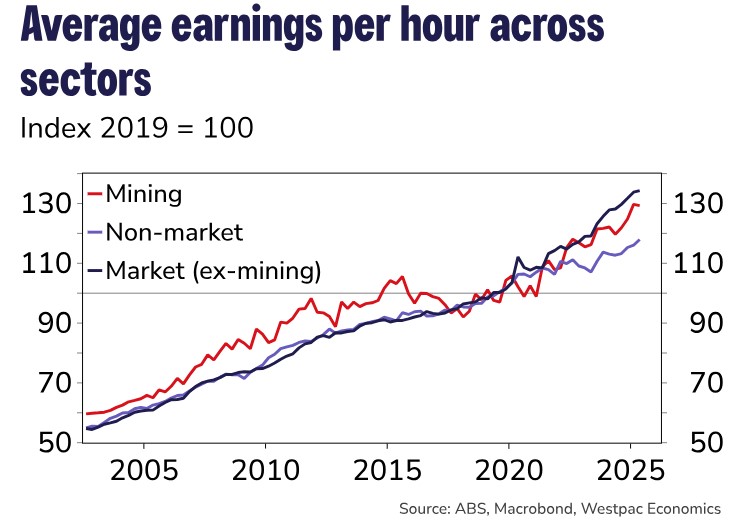

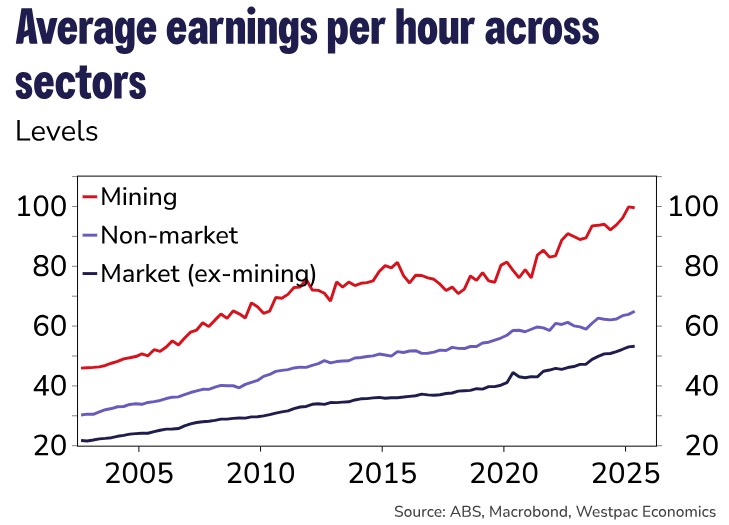

Coming out of the pandemic, growth in average earnings per hour has outperformed in the market (ex-mining) sector growing by more than 30%. This compares to growth of less than 20% in the non-market sector.

However, average earnings per hour remains higher in the non-market sector. This makes sense given the sector is labour intensive and does not have high capital user costs.

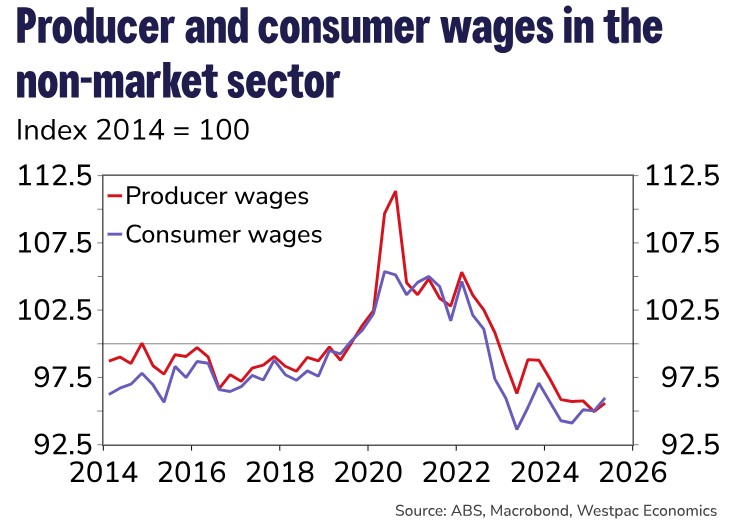

A wedge has opened between producer and consumer wages in the non-market sector. These indices measure how much labour cost producers given selling prices (i.e. higher selling prices makes labour cheaper) and how much workers can buy given inflation (i.e. lower inflation boost purchasing power).

The difference in recent outcomes partly reflects the impacts of government funding and the expansion of programs (such as the NDIS), with government subsidies lowering costs for consumers but supporting revenues for the businesses involved and, in turn, wages growth. In the domestically oriented market sector producer and consumer wages are moving broadly together.

Bottom line

Moderating growth in the economy’s cost base coupled with a reduced ability to pass on costs in higher prices is, from a central bank’s perspective, a sweet spot. It means costs are coming down and demand is soft enough so that these lower costs must be passed on, reducing inflationary pressures. The Q2 National and Labour Accounts also showed that workers are receiving a larger slice of the ‘economic pie’ reflecting several factors including the tighter than average labour market, recent FWC decisions, and evolving wages policy – over the past year this has amounted to around $28 billion in additional income for workers.

Pat Bustamante is a senior economist at Westpac. This is a re-post of the original, which is here.

Comments

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments.

Please to post comments.