There has been a sense of relief in markets and elsewhere at the nomination of Kevin Warsh as the new Federal Reserve Chair. He is not an institutional bomb-thrower, has relevant experience, and is regarded as less explicitly deferential to Mr Trump than Kevin Hassett may have been.

Opinion is split on his policy tendencies. He was a hawk when on the Fed Board during the GFC, arguing against QE. However, his more recent public statements indicate that his hawkish views have moderated. Indeed, it is highly unlikely that Mr Trump would have nominated him unless he had received some assurances in terms of his thinking about Fed policy, at least over the next few years.

Of more relevance is Mr Warsh’s conviction-heavy approach to monetary policy. Rather than relying on available data, which he sees as inevitably backward-looking, his stated preference is to make decisions based on a forward-looking story.

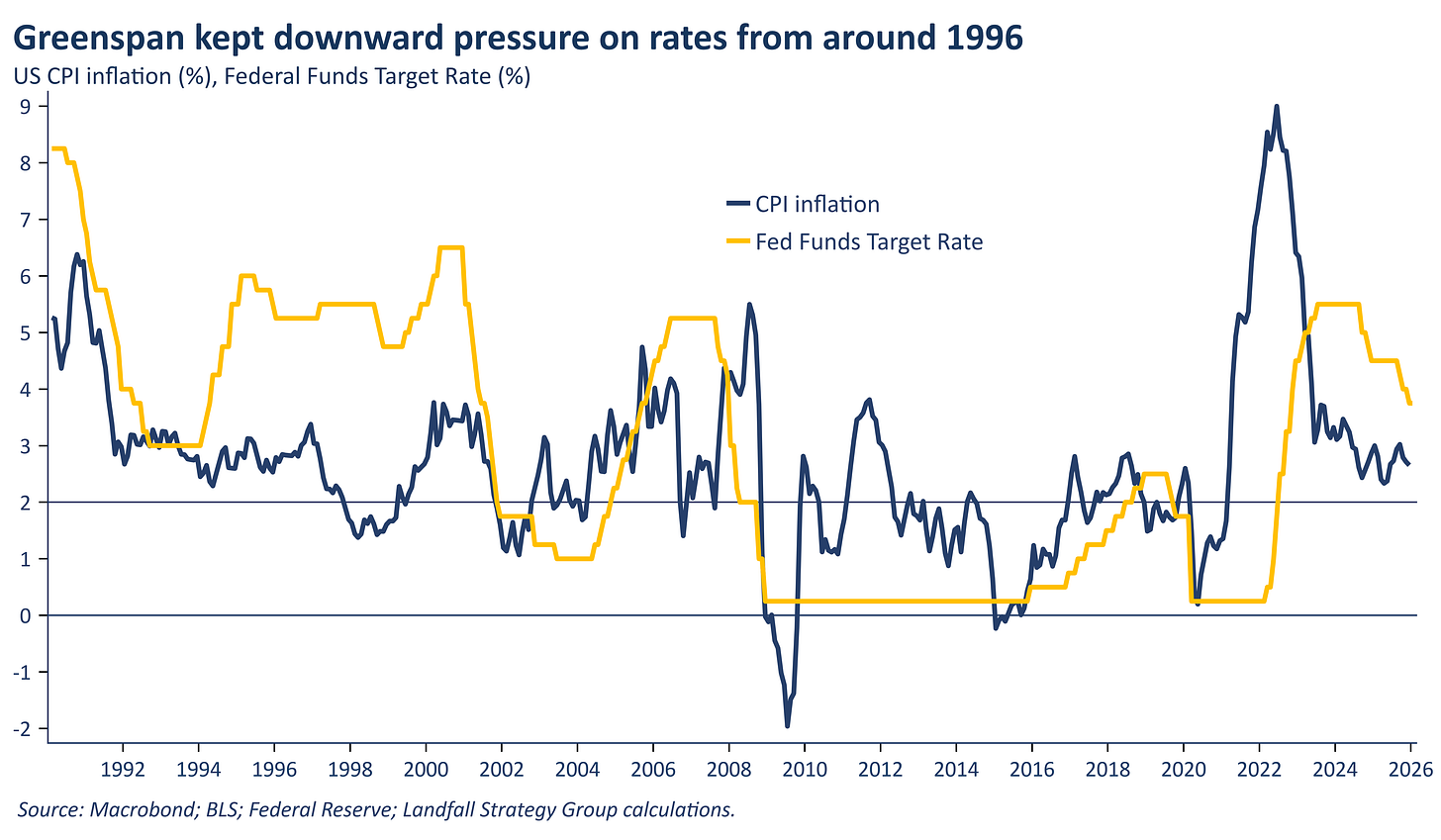

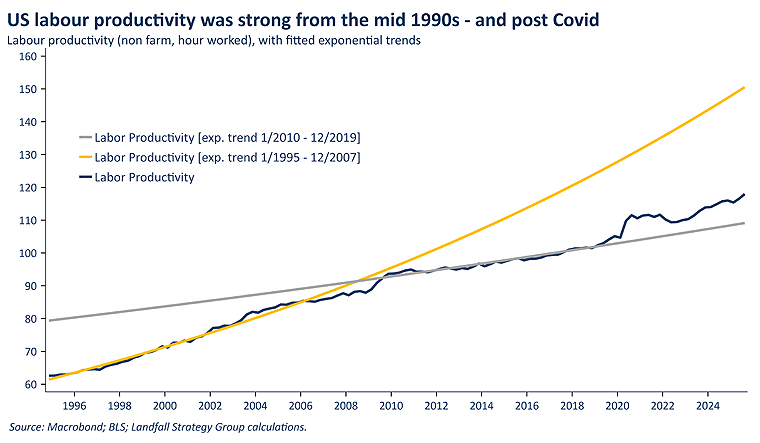

In particular, his recent speeches and writing make it clear that he interprets the current situation as similar to the 1990s, with productivity growth from technology likely to drive inflation down; and believes that a Greenspan-style approach to cutting rates is appropriate.

Reliance on the Greenspan analogy feels like an attempt to put a cloak of intellectual respectability around a preferred policy direction. The only way to be nominated to a Fed leadership role by this Administration is to commit to meaningful rate cuts, even in the context of persistently above target inflation; and the Greenspan analogy is a way to do this in a vaguely credible way.

It is too early to confidently assess the impact of AI and related technologies on inflation and productivity. In the near-term, the build out of data centres is probably inflationary: commodity prices, labour, energy, and so on. However, it is plausible that AI will generate material economy-wide productivity benefits over time. US labour productivity has been above trend since the pandemic, although it is not clear that this is primarily due to AI/technology. Making bold policy choices on a bet that AI will be transformational is premature at best.

Basing policy on a conceptual narrative rather than data can be appropriate in times of structural change. But to do this successfully, the narrative needs to be right. And Mr Warsh’s stated reasoning places too much weight on the specific policy experience of the 1990s, a period with different characteristics.

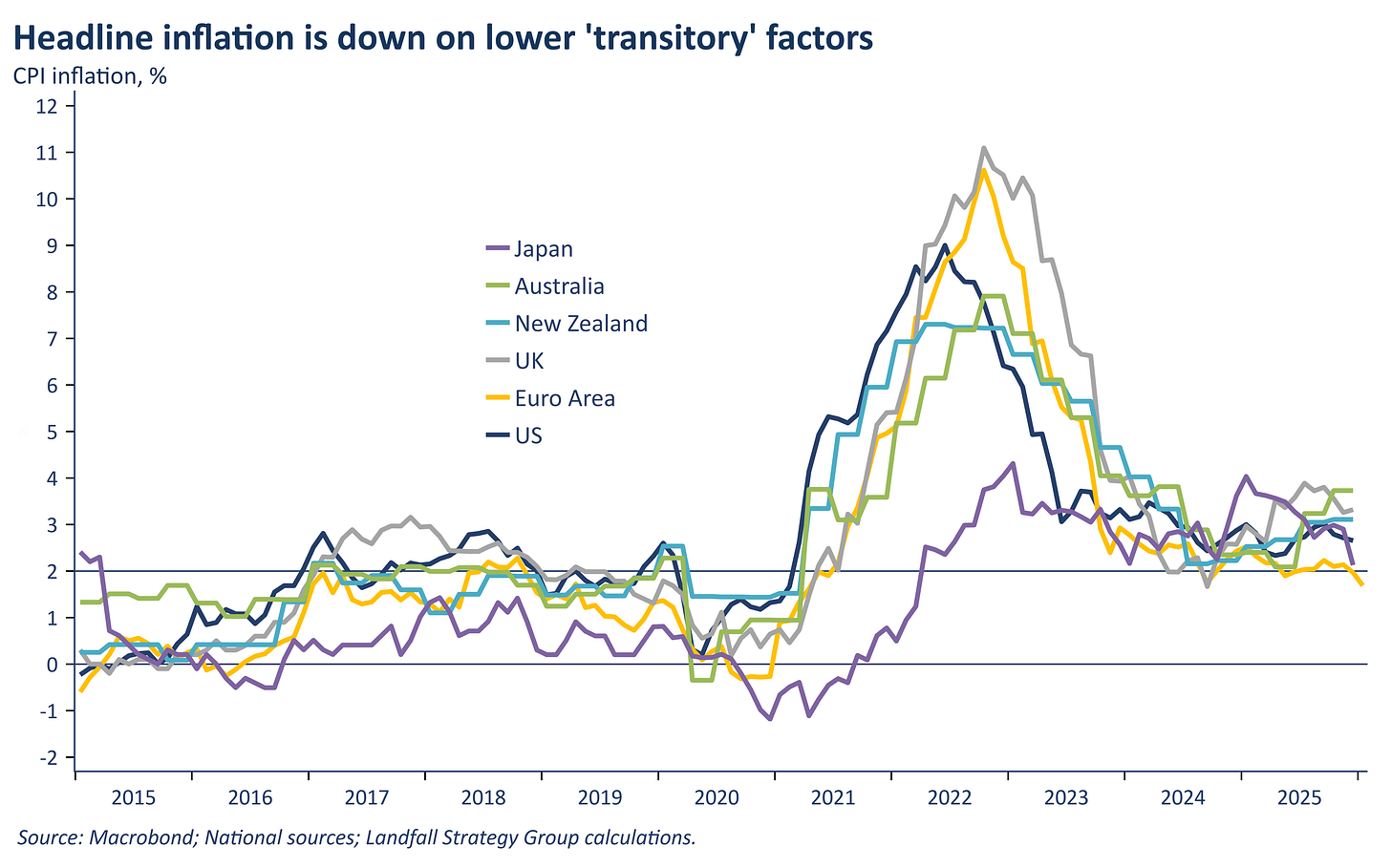

The (worldwide) reduction in inflation from the early 1990s, with policy rates being lowered, was not just due to the deflationary, positive supply-side shock from technology. Other factors contributed as well: the establishment of independent central bank focused on price stability, which lowered inflation expectations; fiscal consolidation across advanced economies (including the post-Cold War peace dividend); the deflationary effects of globalisation; the weakening of worker bargaining power; and so on.

My assessment is that the structural features (independent central banks, geopolitics, globalisation) were markedly more material than technology-led productivity improvements in reducing inflation pressures. Mr Greenspan had policy space to run lower rates that is not available to current Fed decision-makers.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to receive my free public notes on global macro & geopolitics.

In addition, cutting policy rates will be complicated by the process of structural regime change underway in the global economy: from a market state regime towards state capitalism.

The new ‘state capitalism’ regime will be more inflationary. Fiscal policy will be more expansionary (military spending, industrial and innovation policy, and more); commodity prices (ex energy), particularly industrial metals, are rising on capex demand and geopolitically-driven competition for resources; there are additional frictions on global flows, from US tariffs to the redesign of global supply chains to prioritise security rather than efficiency; and there is a levelling off in global labour supply growth, which exerted a deflationary force in the 1990s. History suggests that periods of geopolitical tension and rivalry tend to be more inflationary.

State capitalism will lead to a higher pressure economy, less optimised for efficiency. Inflation is likely to persist in this new environment for structural reasons. Indeed, inflation is holding above the 2% target in most advanced economies (ex Eurozone). Expectations of strong disinflationary tendencies underweight these structural/geopolitical dynamics and over-weight technology/productivity-based dynamics.

This means that the conviction-led policy of Mr Warsh is at significant risk of running monetary policy too loose, contributing to even higher inflation. Indeed, policy settings in the Greenspan era contributed to financial excess and asset price bubbles.

It may be that softening US labour markets in the near-term and productivity-led disinflation over time do create a case for sustained cuts in US policy rates. And US inflation expectations remain relatively stable, suggesting the absence of perceived inflationary pressures. But the structural change underway means that the probability of structurally higher inflation is bigger than Mr Warsh seems to allow.

The new Fed Chair (if confirmed) is likely to push his FOMC colleagues to cut rates more aggressively, despite a robust US economy and inflation above 2%. To this extent, the likely path over the next few years is lower policy rates, a steeper yield curve, and ongoing weakening of the USD. This is the only currently available political equilibrium in the US.

However, regime change means that relying on the 1990s playbook generates a high probability of inappropriately loose monetary policy, leading to even higher inflation and the potential for financial instability over time.

Beyond monetary policy narrowly defined, the scale of the US government’s projected funding requirements will constrain Mr Warsh’s ability to shrink the Fed balance sheet despite his commitments to do so. Instead, my view is that the Fed balance sheet will likely grow as a share of GDP. However, under Mr Warsh’s prospective leadership, watch for potential joint Fed/Treasury action to mobilise private sector financial institutions’ balance sheets in support of strategic industrial policy objectives. This is another example of the way in which Fed policy will be shaped by the regime change towards state capitalism.

This is a shortened version of a more detailed note that I sent to clients, with additional data and analysis. If you would like to discuss access to these regular notes on global macro and geopolitics, together with supporting briefings, please don’t hesitate to reach out: david.skilling@landfallstrategy.com

Thanks for reading small world. This week’s note is free for all to read. If you would like to receive insights on global economic & geopolitical dynamics in your inbox every week, do consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Group & institutional subscriptions are also available: please contact me to discuss options (more information is available here).

*David Skilling ((@dskilling) is director at economic advisory firm Landfall Strategy Group. The original is here. You can subscribe to receive David Skilling’s notes by email here.

Comments

We welcome your comments below. If you are not already registered, please to comment.

Remember we welcome robust, respectful and insightful debate. We don't welcome abusive or defamatory comments and will de-register those repeatedly making such comments.

Please to post comments.